Shrink-wrapping is a process by which a thin film is stretched taut over an object. The closer the film to the object, the tighter the two conform. The term applies the same way when it comes to paleontological reconstruction of formerly living animals. It generally only applies to how thin the skin is, which reveals the underlying tissues in some detail.

The question of paleontology is that: Should you shrink-wrap your fossil animal reconstructions? The answer to this is trickier than it might seem at first. Really, the answer is yes and no. Below I will explain why.

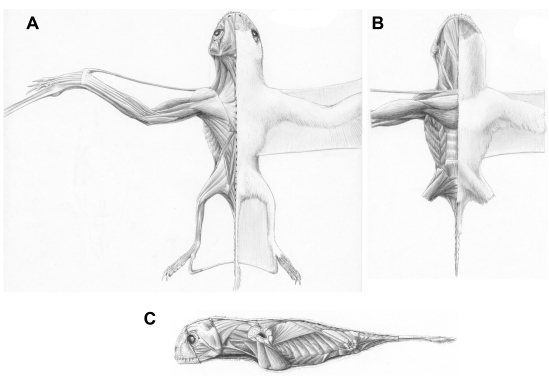

Muscle studies for archosaurs. At top, Hexinlusaurus multidens He & Cai, 1983, Terrestrisuchus gracilis Crush, 1984, Shuvuuia deserti Chiappe, Norell & Clark, 1998, Rinchenia mongoliensis Barsbold, 1986, and at bottom a generic “segnosaur” or therizinosaurid.

What we can say about extinct animals requires study and inference. To do this, we also need to know a lot about the anatomy of their relatives. So it helps to have a comprehensive idea of what relatives you can talk about, and then study those animals’ anatomies to find the right features associated with the right tissues. That way, you can determine how accurate Newmann’s “bat-pterodactyle” or Waterhouse’s Megalosaurus really are.

A recent trend in paleontologically-themed art (as indeed, with much art of extinct animals) has been to render the skin and integument over the body as though it were taut, tight and rigid. As anatomists, this is hard to avoid: We want to show our work. But as zoologists, we have problems, because this doesn’t always match up with the real thing. Or what we think of it. We can go the other way, and just draw modifications on a known animal to make a tiger or lion a “sabre-toothed” version (like much of the past depictions of machairodontine cats had shown them).

Of late, when it comes to the drawing of dinosaurs and the debate over integument rages (as it sorta also does for pterosaurs), the issue how how much skin and how it’s shaped over the body has come up. The issue of shrink-wrapping is thus of some concern. Not only does it matter if you never want to put feathers on your animal, it matters when you do because this is the layer of flesh in which those feathers begin. Thus starting from muscle alone is not enough.

For the last few years, we’ve become even more aware of how much the flesh we draw doesn’t match what we should be drawing. The caudofemoralis, for example, is a very, very big set of muscles behind the thigh, and it’s bulging should be noticeable. The face isn’t always a direct conform to the underlying skull. These things I’ve said before. So this post had me thinking about where and when one should shrink-wrap. And yes, you should.

But it depends where.

If you look at modern animals today, you will notice that most them them don’t have bulging muscles in their hands and feet. There are fatty deposits and cutaneous pads and whatnot, but muscles? Aside from the tendons connecting muscle bellies to bones, hands, feet and faces tend to be without these things. So in birds and crocs and mammals and lizards, these regions of the body tend not to conform to underlying muscle structure. Instead, they match other tissues, including bone. Get closer to the body core, and things become different. Not only are muscles more apparent, any other tissues of the body will become more so. Birds have air-sacs leading from their thoracic and abdominal cavity in their very skin, reaching into their arms and legs, while the muscles of these regions are heavy and obscure the underlying bone. Sometimes the skin matches those muscles, but often they don’t. Fat is there, too, and it also varies.

If you look at modern animals today, you will notice that most them them don’t have bulging muscles in their hands and feet. There are fatty deposits and cutaneous pads and whatnot, but muscles? Aside from the tendons connecting muscle bellies to bones, hands, feet and faces tend to be without these things. So in birds and crocs and mammals and lizards, these regions of the body tend not to conform to underlying muscle structure. Instead, they match other tissues, including bone. Get closer to the body core, and things become different. Not only are muscles more apparent, any other tissues of the body will become more so. Birds have air-sacs leading from their thoracic and abdominal cavity in their very skin, reaching into their arms and legs, while the muscles of these regions are heavy and obscure the underlying bone. Sometimes the skin matches those muscles, but often they don’t. Fat is there, too, and it also varies.

The above illustration is meant to depict my fave oviraptorosaur “Ingenia” yanhsini as a muscle/tendon only and as skin/beak/claw only. Tissues leading away from the body core become increasingly more prone to matching the underlying tissues, although this differs in the tails of some sauropsids, especially birds, mosasaurs, and ichythyosaurs. The face does a 180 and tissue nonconformity increases around the oral margin (and for display structures) from the underlying hard tissues — though in some predictable ways.

Marine reptiles are a little tricky in this regards. The distal limbs actually become LESS like the underlying bone structure than the proximal limbs because the tissues seem to support extensive soft-tissue forming paddles. Marine reptiles also seem to have fairly nondescript, barrel-like torsos, grading somewhat smoothly (or not?) into neck and tail. There it becomes trickier, and the issue of soft-tissue around the neck problematic. Short necks may be thick, long necks thin, and the tissues less and more conforming respectively. But how? The problem with necks is that not all necks are alike, and even when they are the phylogenetic relationships may not help confirm suppositions. Elasmosaur necks arise from within groups of short-necked sauropterygians, and sauropods and birds convergently acquire extremely long necks, inviting much comparison. But elasmosaurs are also marine, and likely not requiring the stiffening attributes of ornithodiran long-necked animals. And of course, there’s pterosaur necks, much of which have received scant analysis on the muscles that surround them.

For the shorter-necked, larger-headed pterosaurs, muscles of the superficial layers hide the deep-layer problems we’re faced with, Longer-necked pterosaurs stretch these tissues out, and it is possible they become more tendinous as the need to move side to side or up and down becomes less possible, as seems to be the case with some azhdarchids. A stiff neck moves passively, needing less muscle, and thus the surrounding tissue is spared towards other things. This may be the case in sauropods, for which individual vertebral mobility is limited, and thus curvature and bending may be controlled at the proximal ends of the neck, at the shoulder. This is similar to how the operation of the legs in many quadrupeds function. For grasping animals, higher densities of muscle bellies are linked to individual tendons in the digits, which helps them be mobile, but still controlled from the proximal (forearm) position of those bellies. So it’s likely that necks, when long, are closer to the underlying structures than are short necks.

And when it comes to the head, well, one has merely to look at a bird with not much feathers on its head:

Some features match the underlying bone, especially on the sides where the bony naris, preorbital openings and even bony orbital rim are visible. In the rear of the jaw, not so much, as the muscles obscure this, as well as the auricle (tissues around the opening into the ear canal). The bottom of the jaw is clear, and the edge of it at the back matches the processes of the jaw-opening mechanisms. But the jaw margins are not, as they are covered in beak, and then there’s that casque, which doesn’t precisely match the underlying bone, as also seen in hornbills (and in some birds with a casque like this, there’s no bone at all to suggest the shape of the final structure).

So when it comes to wrapping a skin around the animal, a tight skin is useful in some parts of the body (where muscles aren’t needed as much), but not when other tissues imply otherwise (thickening the tail for the support of feathers, broadening the hand or foot to form a paddle, or around the jaw margin). This tells us then that we can shrink wrap some parts of the animal, but not so much others.

That is fascinating….I wondered if there was a method to the madness of dinosaur artistic rendering.

Thank you! Finally someone talking about the amount of “flesh” or lack there of in particular areas of prehistoric animals. I love the Ingenia muscle study, well done! I thought I would mention, in art school while learning figure drawing they teach you to learn the “bony landmarks”. It is interesting because humans can tend to be fairly “fleshy”, yet the bony landmarks are still present and represented by the overlying “flesh” even in “rotund” models. I often wonder how much tissue it would take to completely obscure the forms below. Obviously in extreme cases it can be pretty well obscured. I have often wondered how bony landmarks could apply to other animals particularly dinosaurs and the like. Some are fairly apparent in extant animals as well, “I’m thinking horse and dog” http://www.lovehorsebackriding.com/anatomy-of-a-horse.html. Obviously mammals aren’t the best anlogue, but I imagine reptiles and birds haven’t received the same amount of attention as man’s two best friends. Also, if you compare the skulls of Crocodilians to their fleshed out counterparts you can see where the skull influences the skin above. Obviously it may be less apparent in other areas if you don’t know what to look for. Well, thanks again! This post and your others are very valuable to other artists, so keep em coming!

I just took a taxidermy class this weekend, using starlings. Sure enough the only parts we left any of the skeleton in were the yellow parts in your diagram (plus the keratinous areas).