A foggy morning. Water laps gently on a rocky shore, a rhythmic sound accompanying the gentle hum of insects. Mist hugs the forest margin, creeping along the ground; it shrinks back as the heat of the rising sun burns away the last remnants of night. From the fog steps a bizarre sight: a long legged, quadrupedal animal, the forelimbs are huge, a long spar folded against the arm and projecting upwards. At the end of a short, thick neck is a large head, surmounted by round crest. The head ends in a narrow point, and the tip of the jaws curve upwards. The edges of the jaw gleam in the light, the beak extends along the length of the mouth – there are no teeth.

A Bust of Banguela oberlii, not done in a super serious manner. We’ll get to a better image down the road.

This is Banguela oberlii, and it is Brazil’s newest pterosaur, described by myself and Hebert Campos just today in Historical Biology. It had a head almost two feet long, and a wing span over twelve. It would have weighed as much as a small dog, or a large goose. Long wings, tightly folded, and long legs with thick angles. A forthcoming post will describe the anatomy of this new pterosaur in detail, as well as the story of its “coming out.” Stay tuned for that.

Banguela oberlii is a dsungaripterid, a group of pterosaurs with unusually thick bones, robust jaws, and thick teeth. But Banguela oberlii has no teeth, making it a very different kind of dsungaripterid. Only three groups of pterosaurs were known to completely lose teeth: pteranodontids and nyctosaurids, with long, deep beaks, and a collection of the huge-headed, long-necked pterosaurs called Azhdarchoidea: azhdarchids, including Quetzalcoatlus, the bizarre-nosed chaoyangopterids, and a group which includes the tall-crested tapejarids and the long-crested thalassodromids. Pteranodontids aren’t known from Brazil, and nyctosaurids might be represented by the partial remains of Nyctosaurus lamegoi (Price, 1953) but due to their phylogenetic relationships they had similar, but toothier, relatives.

~

An inquisitive look around, the pterosaur scans for signs of one of the tiny fuzzy horrors it must avoid, Mirischia. Far larger are the more irritating spinosaurs, and instead of being a mobbing coelurosaur they will attack even the largest pterosaurs. But the coast is clear, literally.

Tide pools remain as the water recedes from the shore. Food is left there, fish and occasionally turtles, as easy to come by as one might wish. Craning upwards, a quick look around, then down. The sharp bill probes into the water. Snap a large fish from the pool – a lucky find – the Banguela tosses it into the air. The tips of its jaws are thin, blade-like: they are not good for holding food. It catches the fish in the back of the where the sides of the jaw are turned into pairs of blades, far more suitable at holding food. The food in the back of the throat, the head point up, the fish is swallowed whole, head first. The spiny barbs of fish point backwards, so it’s much easier this way. Back down to the pool. Nothing interesting in there; nothing big. Off to the next pool.

Morning fog burning off, the sun rises higher. The spinosaurs will be out soon, time to make the best of it … before the other pterosaurs of Santana arrive.

~

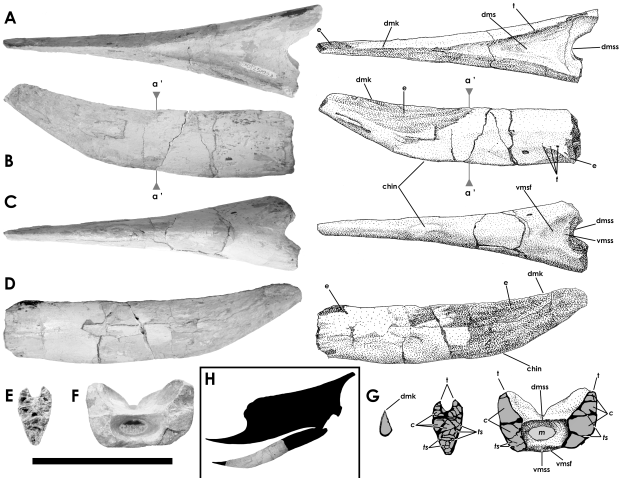

Compound figure from the paper, with an inset box that isn’t. All that we know of Banguela oberlii, to date, is from this fragment of the jaw. The skull, however, was rather large.

When the jaw that would become Banguela oberlii was first discovered, researchers though it might belong to a pterosaur that had been described three years earlier: Thalassodromeus sethi, “Set’s sea runner.” Thalassodromeus sethi is an azhdarchoid, one related to the almost silly-looking Tapejara wellnhoferi. Those similarities are there, but they are limited. There are more differences than similarities, and those differences point to a different relationship. Scientists use a number of techniques to find out relationships among animals, and one of these – phylogenetic analysis using cladistics – is particularly useful. These techniques our study found pointed in a different direction, one where the short, upturned jaw had many similarities to dsungaripterids. As I said, dsunagripterids normally have teeth, and that poses somewhat of a problem.

An interesting rule of biology says when animals lose a feature, it cannot be regained. This is called Dollo’s Law, and it tells us about why birds don’t regrow teeth. (On their own, I should add. Teeth have been grafted onto their jaws, or forced to grow by chemical shenanigans, but as a natural process, without human intervention, this doesn’t happen.) Many analyses find dsungaripterids at the base of the azhdarchoids, but some find them deeply nested among the toothless forms. These imply multiple periods of tooth loss, and not one of these studies suggests how. Dsungaripterids, however, hint already at a method: gradual reduction from the tip of the snout. Slowly, surely, the teeth become fewer and fewer, the jaw longer and longer without teeth. Taken in context, Banguela oberlii is the culmination of this trend.

Pteranodontids and nyctosaurids have been found at the base of Ornithocheiroidea (or, in some formulations, this is termed Pteranodontia) which are typically filled with toothy, wicked maws. Instead, the reverse is suggested: basal pteranodontids, nyctosaurids lack teeth; intermediate istiodactylids have few teeth clustered at the jaw tips; and toothy anhanguerids/ornithocheirids and lonchodraconids have fully toothed maws. Probably, pteranodontids and nyctosaurids developed their toothlessness independently and — as they are rarely found as each others closest relatives — convergently to one another. This, then, suggests that pterosaurs lost teeth a minimum of four times: the azhdarchid, chaoyangopterid, thalassodromid/tapejarid clade, pteranodontids, nyctosaurids, and apparently dsungaripterids.

Our pterosaur’s name means “toothless” in Portuguese. It’s used to describe older people whose teeth are falling out. Grandmother, baba, babushka. Affectionate.

Possible skull reconstruction for Banguela oberlii, with the holotype jaw in full color. Banguela oberlii is here hypothesized to be a derived dsungaripterid, though in our phylogenetic analysis (Headden & Campos, 2014) the new taxon was placed basal to other dsungaripterids. Further analysis supports a deeper nesting, but this work was not prepared at the time of publication.

There’s just one bone known of Banguela oberlii: NMSG SAO 251093, which is the front half of both jaw bones, fused together along the middle in what’s termed the mandibular symphysis. This feature turns out to be very important, but under-studied feature in pterosaurs.

The jaw isn’t complete; it’s only 40% of its total projected length, but this tells us the animal had a head nearly 2 feet long, a body almost 6 feet long, and a wingspan twice that. Despite its incompleteness, what is amazing when working on comparing the jaw to other pterosaurs is how much we could know. We added new data to pterosaur studies, and looked deeper into pterosaur jaw morphology. An early draft of our paper had a lot to say about the features we were looking at, and a figure of the paper shows all the crazy stuff going on. And that’s just between these animals. I would have to include a lot more little data points, over thirty characters to consider, to try to capture the sense of diversity involved. And I think that would be far too few.

~

Banguela oberlii walks off into the morning in search of food, an eye kept out for danger. While its head is down, beak pushing into the muck of a pool, thin jaw nudging a stone over in search of some soft animal. A smell … a spinosaur? Too late.

The rendered bits of body of our pterosaur drift down into the murk of the lagoon’s waters. Here, the water is poorly oxygenated. The water is still, the currents from the ocean do not mix much, and the oxygen has become depleted. Without oxygen, only some life remains, much of it scavengers that feed on the animals foolish enough to arrive here on their own, or unfortunate enough to be sent here. What the spinosaur did not take with it, including long bones with meat on them or nutritious, fibrous wing membranes, washes into the deep pools of the anoxic lagoon bottom.

Here, time will take its toll. The sediment is rich with decay, a silty sand that will harden and compress into layers of sandstone. In it, concretions of rock (nodules made of carbonates like limestone) form around pterosaurs, insects, fish; layer by layer, accumulating over a long time, with the original element embedded within, a process akin to the formation of a pearl. Even our hungry spinosaur will join these one day. Banguela oberlii will be but fragments of its former self, but someone will find it, open the stone, and find what will one day become “the toothless one.”

Headden, J. A. & Campos, H. B. N. 2014. An unusual edentulous pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous Romualdo Formation of Brazil. Historical Biology [Published online ahead of print]: 1-13. doi: 10.1080/08912963.2014.904302

Price, L. I. 1953. A presença de Pterosauria no Cretáceo Superior do Estado da Paraíba [Prescence of pterosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous of Paraíba State]. Notas Preliminares e Estudos, Divisão de Geologia e Mineralogia, Brasil 71: 1-10.

Wow, congrats Jaime – first paper?

Yes, it is. Paper almost didn’t happen, so it’s a good thing to see it out and done.

This is really cool Jaime! I really hope this will lead you to write many more scientific papers in the future. You and Mickey Mortimer deserve to publish much of the text you already wrote on your blogs.

Congratulations on your first paper, Jaime! Hope it isn’t your last.

I’m very curious about reading something more about Banguela, it’s a wonderful specimen.

There’s more to say. Actually discussing the fossil and a jaw bone and what that means will be a bit down the road.

Nice to see it finally published!

With no little thanks to you, as well.

I think you nailed it. Congrats!

Very nice! Congratulations!

Good job! Congratulations!

Congrats!

A rather unusual critter indeed. Dsungaripteroids have some of the most specialised dental anatomy of all sauropsids, so Banguela must have been doing something really different to simply discard it’s teeth like that.

Pingback: The Broken Jaw of Banguela | The Bite Stuff

Congratulations on your first paper! Now, I’ll be following your follow up posts on it.

Pingback: Banguela: a new pterosaur by a first-time author | The Pterosaur Heresies

Due to a potentially confusing passage on Dollo’s Law, I added a more filled out paragraph on the subject and why it’s there. The topic is only passingly referred to in the paper.

Pingback: An Edentulous Dsungaripterid? 10 Facts About Banguela | The Bite Stuff

Pingback: A Look Back at the Bite Stuff, 2014 Edition | The Bite Stuff

Pingback: Is Banguela na invalid taxon? – pterosaurologist