There is much we still do not know about the ancient origins of birds and near-bird animals, dromaeosaurs and troodontids. As we find more specimens of archaeopterygid or scansoriopterygid-like animals, of Anchiornises and what not, the tree becomes more of a bush, chaotic, involuted, interesting.

The Maastrichtian of Romania reveals a series of islands in what is now eastern Europe, the last remnants of the epicontinental sea that covers Europe diminishing as Africa looms closer to the south, rotating upwards and lifting the Alps of southern Europe. These islands formed intriguing biotas, comprised of small herbivorous ankylosaurs, hadrosaurs, pro-iguanodonts, and sauropods; and large birds and pterosaurs. The largest predators of these islands were probably azhdarchid pterosaurs. But amongst them, the small cat-sized Balaur bondoc is also known.

Found in the Sebeș Formation of western Romania, the only specimens of this small animal pertain to what seems to be an incredibly robust-limbed dromaeosaur. While initially speculated to be of a oviraptorosaur, it was later described as a unique, stocky dromaeosaurid, and the name chosen to reflect local Romanian folklore: Balaur bondoc means “stocky dragon,” with balaur [n1] referring to a draconic creature, whose saliva could form gemstones. Dromaeosaurs from elsewhere in Europe had been known, with Variraptor mechinorum (and possibly Pyroraptor olympius) being ambiguous contender, both from southern France. While these have had their relationships questioned, Balaur bondoc has benefitted from a robust preservation, including nearly complete forelimbs, hindlimbs, and sections of rib, pelvis, shoulder, and many vertebrae. Enough to gain a good picture of the animal.

Found in the Sebeș Formation of western Romania, the only specimens of this small animal pertain to what seems to be an incredibly robust-limbed dromaeosaur. While initially speculated to be of a oviraptorosaur, it was later described as a unique, stocky dromaeosaurid, and the name chosen to reflect local Romanian folklore: Balaur bondoc means “stocky dragon,” with balaur [n1] referring to a draconic creature, whose saliva could form gemstones. Dromaeosaurs from elsewhere in Europe had been known, with Variraptor mechinorum (and possibly Pyroraptor olympius) being ambiguous contender, both from southern France. While these have had their relationships questioned, Balaur bondoc has benefitted from a robust preservation, including nearly complete forelimbs, hindlimbs, and sections of rib, pelvis, shoulder, and many vertebrae. Enough to gain a good picture of the animal.

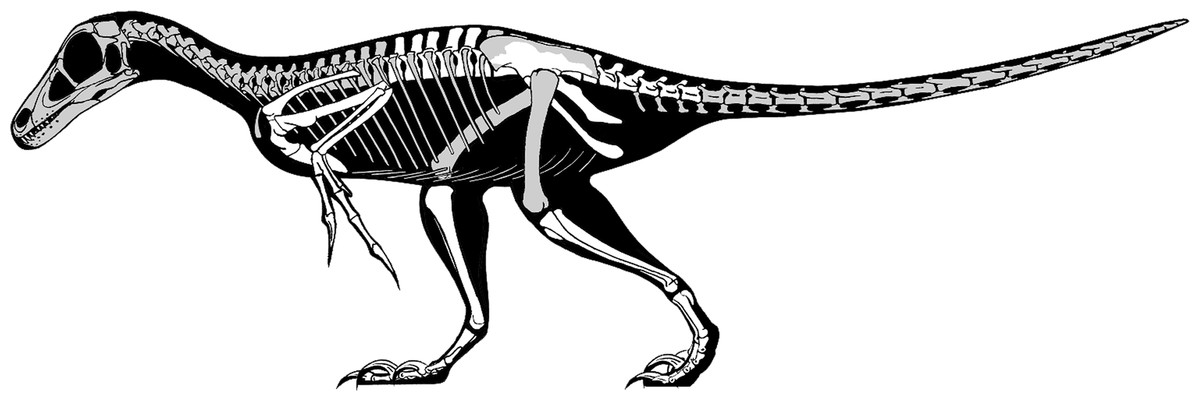

Sometime later, I started work on a skeletal reconstruction. I didn’t get very far when I was asked to possibly take into account some unusual findings. That person, Andrea Cau, was preparing some data that purported a different relationship. So, eager, I began to approach the skeletal differently than I had before, with a mind to both ideas. The result lies below: A paravian Balaur bondoc.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This skeletal illustration differs from others in the distinct form of the skull and tail, deliberate choices to allude to its paravian relationships: A shorter tail with fewer vertebrae, lacking the elongate rods so distinctive of dromaeosaurids; a shoulder with a large, raft-like sternum; and a head that doesn’t sport large, wicked teeth for the rending and tearing of gorey bits. It’s more sedate; Andrea and I chose a pose that wouldn’t detract from the skeleton, so it’s not as dynamic as it could be. It’s meant to show off the various bits. I’ve folded the arm roe bird-like, and pulled the foot claws all onto the ground with a first toe that bore the weight of the animal.

This illustration has now found its way into publication, in a paper by Andrea, and colleagues Tom Brougham and Darren Naish. In their work, they find ample support for a placement within basal Avialae rather than amongst Dromaeosauridae, and that critical features of dromaeosaurids are lacking. Moreover, the odd placement indicates many features are more unusual and reflect something we’ve suspected about island inhabitants, namely Foster’s Rule, in which small animals in isolated areas become larger (the rule, also called the island rule, also seeks to explain dwarfism, which also occurred in the ancient Romanian islands). This same rule explains some of the largest parrots (kakapo and kea), lizards (monitors, such as Varanus priscus), and pigeons (dodos and solitaires) to crunch through the undergrowth of any island. As a descendant of small avialan birds, the largest of which otherwise only got to small hawk size and only in eastern China, Balaur bondoc indicates a highly terrestrialized “near-bird” with shrunk forelimbs, legs, that bear the remnants of its ancestry. It is perhaps one of the most fascinating theropods outside of oviraptorosaurs (for me).

From the paper, “Speculative skeletal reconstruction for Balaur bondoc, showing known elements in white and unknown elements in grey. Note that the integument would presumably have substantially altered the outline of the animal in life.” (from Cau, Broughham & Naish, 2015.) Art by me, modified with permission.

But rather than rehash too much, go read the paper, which is free! Further, Andrea has a post up on his blog on the subject, featuring the beautiful art of Emily Willoughby (it’s written in Italian, but Google Translate, which Andrea provides a link for, does a good job with it).

[n1] I previously used the pronunciation “bell-AR,” largely in keeping with the foreign origin of the world. Rather than digging back through roots, the standard practice is being favored instead, which is to pronounce it as the authors do, which is in standard Romanian. Thus, pronunciation is as David below in the comments indicates: “bahl-OUR.”

Cau, A., Brougham, T. & Naish. 2015. The phylogenetic affinities of the bizarre Late Cretaceous Romanian theropod Balaur bondoc (Dinosauria, Maniraptora): dromaeosaurid or flightless bird? PeerJ 3: e1032.

Csiki Z, Vremir M, Brusatte SL, Norell MA. 2010. An aberrant island-dwelling theropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Romania. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107: 15357-15361.

Varanus priscus as an example of the island rule? Do you count Australia as an island in the biogeographic sense, despite the presence of Thylacoleo and Thylacinus (and perhaps Quinkana)?

Of course not: Romanian doesn’t pronounce all unstressed vowels the same, and au is a diphthong just as it’s written. Try bahl-OUR.

I was actually looking not into Romanian as the root language from which it derives. I was trying to denote a distinction between the root “dracu” in Romanian and the introduced “bală” from which “balaur” comes. Since the latter was historically tied to a particular type of creature, I take it more to be a folklorish name, much as “olm,” “worm,” “wyvern,” or “soukhos” have particular concepts that are unique to them but got conflated with “dragon.” I translate it as dragon because that’s how it’s intended, but even the wiki notes that the comparison is possibly coincidenal.

We (as in, including our Romain colleagues) do indeed pronounce it ‘bahl-OUR’.

Ah, I will correct.

Thank you, auto-correct. For ‘Romain’, please read ‘Romanian’!!

Cool skeletal Jaime. Given the front-heavy nature of the animal I’m surprised you didn’t leave the femur a bit further forward for a more knee-driven walking style?

My original plan was to rotate the body upward in more “standard” Jaime, then pull the arms out. Tucking the arms in and pulling the body down, after discussion with Andrea, was meant to be more subtle. None of my Rockettes high kickers. The body does seem a bit front heavy, but the limb design doesn’t seem terribly prone to knee walking: the femur is still rather long in comparison to the torso. For such a squat leg and obvious terrestrial gait, yucking the knee would drastically lower the body, so I decided not to go Dachshund on it.

Fair enough on the logic, although the femora aren’t known in Balaur, are they?

Ugh. I think I’m really tired right now. You’re correct.

I think I assumed femora of equal length to the shin in order to minimize assumptions, since it’s similar to Shenzhouraptor. I could have extended femoral length (mediportalism possible), but no matter. If the femur is shorter, it might be more of an issue, with even shorter legs, as knee-walking.

ok, I need to brain more before I unbrain….

Great skeletal! The idea of an arboreal flightless ave living during the Late Cretaceous is pretty interesting, especially if you factor in that Balaur co-existed with large azhdarchids. I can only imagine a flock of “stocky dragons” navigating through the trees, fleeing from a gigantic azhdarchid pursuer.

Pingback: PaleoNews #15 | An Odyssey of Time